“ The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back toward slavery .”

— W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America

The Wilson Administration

Our history books tell us that President Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the first progressive Democrat of the twentieth century and an exemplar for the future generations of liberal policymakers and Presidential administrations that would succeed him.

He was the first President to have earned a Ph.D. A professor at Princeton University and then as its president, Wilson had a meteoritic rise to political power. After a mere two years as Governor of New Jersey, Wilson defeated both William Taft and Theodore Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1912.

Wilson did away with a tariff system that favored the rich. He created the Federal Reserve that led to banking reform enabling farmers in the West and the South to borrow on lines of credit. Wilson established antitrust laws, made it possible for workers to organize and participate in collective bargaining, advocated for an eight-hour work day (and forty-hour work week), and though reluctant at first, became an eventual supporter of women's suffrage and the 19th Amendment.

Following the devastation of World War I, Wilson was instrumental in organizing the League of Nations, with the goal of cooperatively resolving international disputes and preventing wars. But resistance by a Republican-controlled U.S. Senate, the determination of European leaders to punish Germany, and the stroke he suffered in the last year-and-a-half of his presidency prevented ratification.

While running for president in 1912, Woodrow Wilson addressed to a letter to a prominent black church official, writing: “Should I become President of the United States you may count upon me for absolute fair dealing for everything by which I could assist in advancing the interests of the race.” But once elected, he did the opposite.

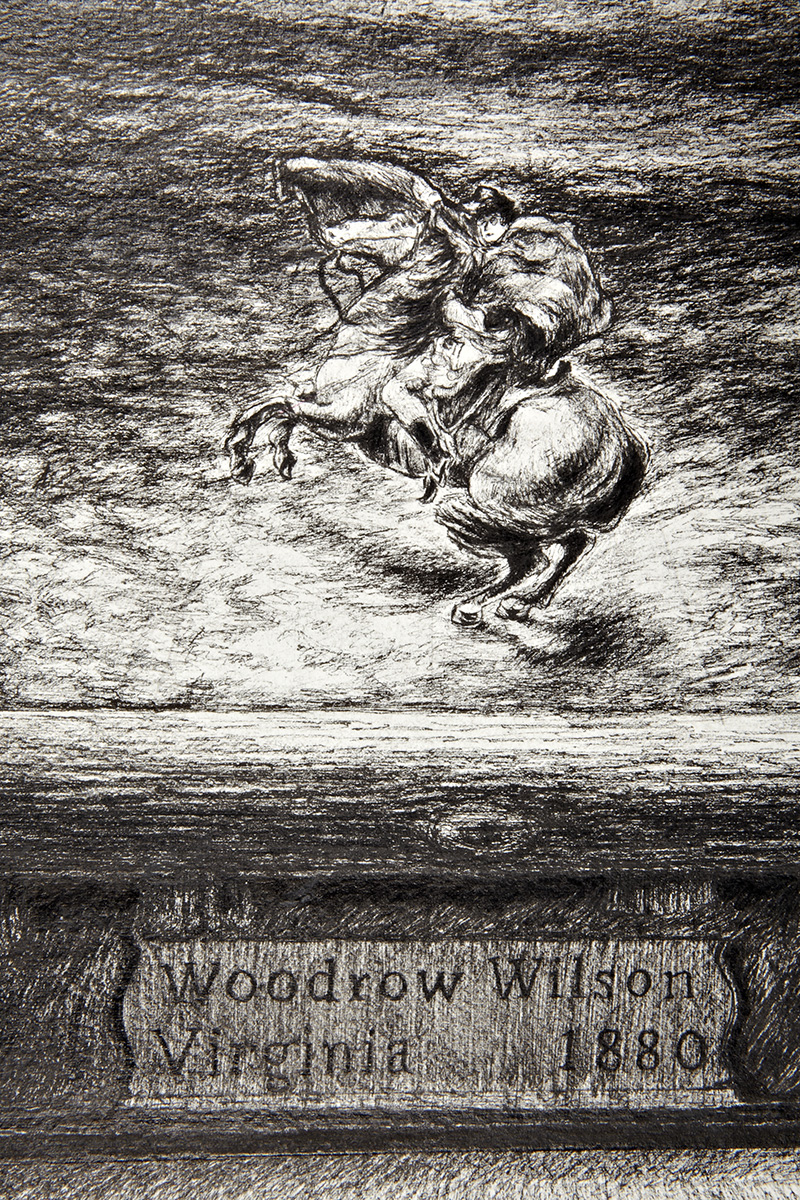

Born in Virginia in 1856, the son of a Confederate Army chaplain, Wilson had witnessed Robert E. Lee in the custody of Union soldiers after his surrender in Appomattox in 1865. Wilson, always a loyal Southerner, spent his formative years in Georgia and South and North Carolina. He never was able to transcend his antebellum upbringing. His administration endorsed the Racialist Movement of the teens, the popular form of eugenics that played a critical role in forming U.S. immigration policy and anti-miscegenation laws. Wilson’s policies either condoned or openly advocated Jim Crow laws, segregation, and racial supremacy.

Three drawings in this body of work look critically at the Wilson legacy.

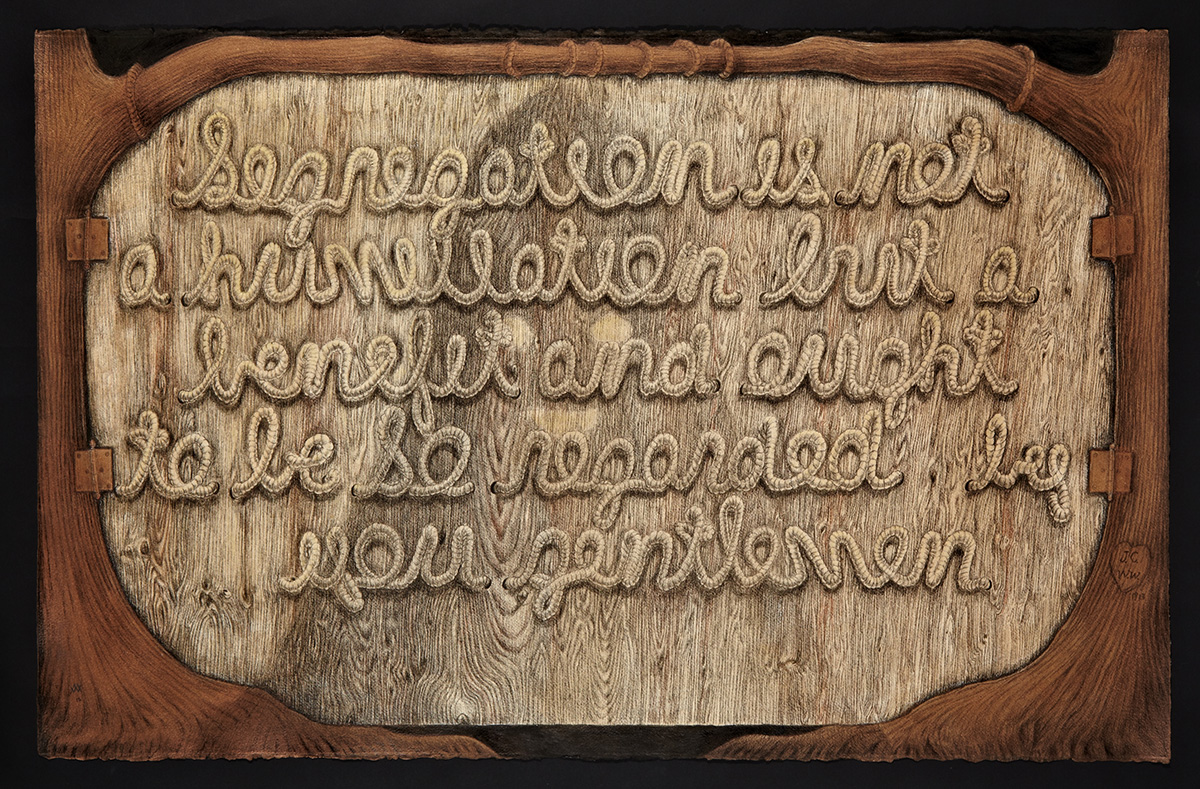

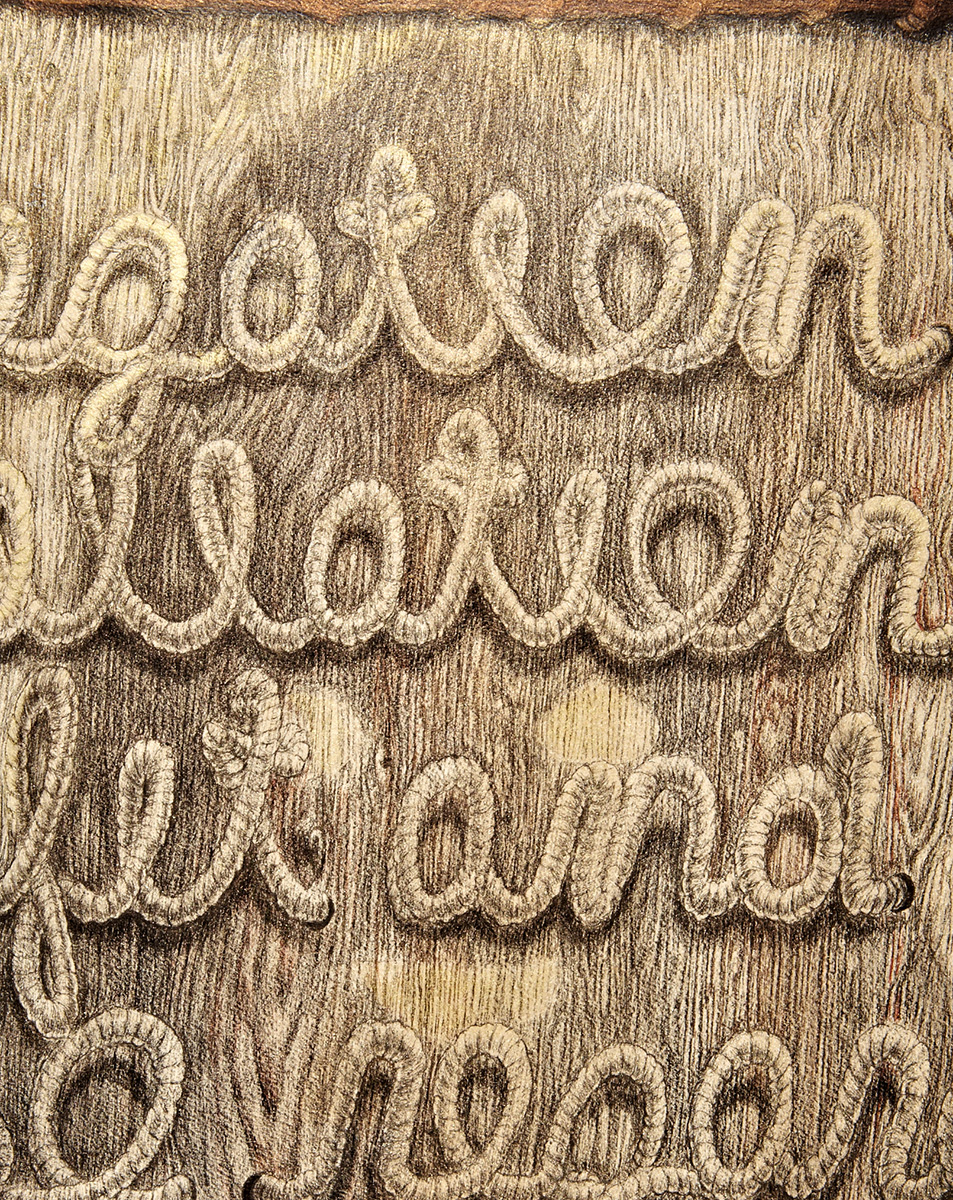

Down in Washington City 1913 (2015)

One of Wilson’s first executive orders was to have his cabinet heads re-segregate government offices in which blacks were employed. As African-American leaders reproved his policies, he responded (rendered in rope cursive form here), “Segregation is not a humiliation, but a benefit and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen.”

In 1913, Washington was a fiercely segregated town but government offices were one of the few exceptions. They had been integrated during the period of post-war Radical Reconstruction as an effort to enable blacks to obtain federal jobs and to work with whites in various government agencies. Wilson quickly reversed these progressive policies and dismissed fifteen of the seventeen black supervisors replacing them with whites. Not only were cafeterias and restrooms segregated, but screens were set up in many federal offices to separate African-American workers from whites. Advancement, once possible under previous Republican administrations, was now virtually impossible.

He filled cabinet posts with Southerners who were intent on undoing the last remnants of Reconstruction. Throughout the country, blacks were dismissed from federal positions or segregated from their white cohorts. In Georgia the head of the Internal Revenue Service fired all black employees, stating, “ There are no government positions for Negroes in the South. A Negro’s place is in the cornfields.”

In his magazine, The Crisis, W.E.B. Du Bois bitterly remarked, “The federal government has set the colored apart as if mere contact with them were contamination. Behind screens and closed doors, they now sit as though leprous.”

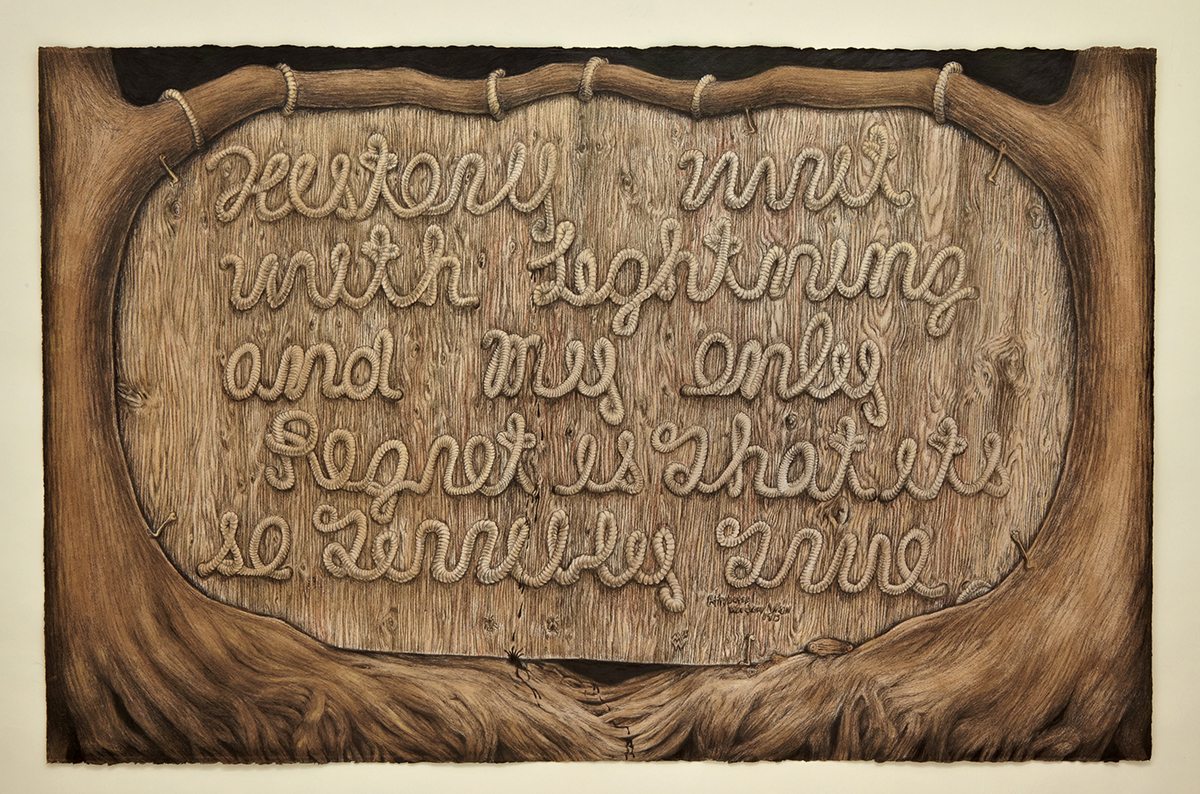

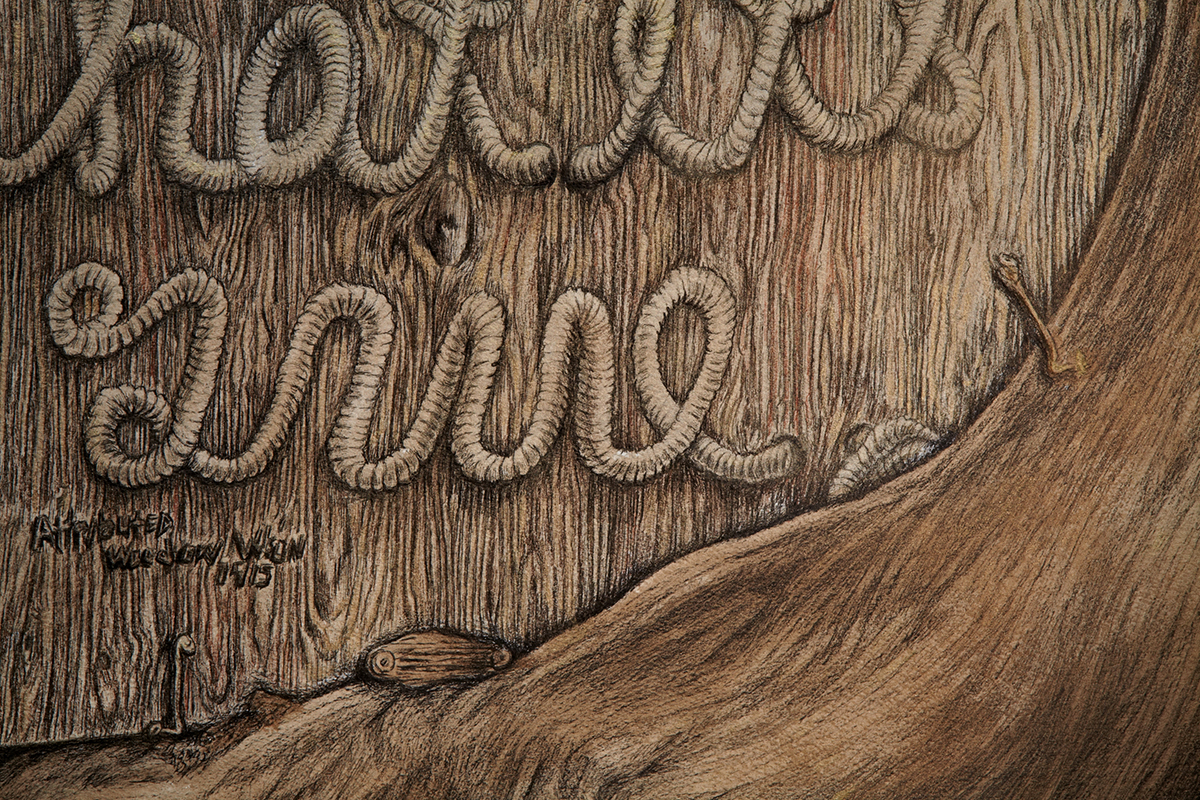

Birth of a Nation (2015)

Birth of a Nation captures Wilson's reported comments after a private viewing of the 1915 film by the same name. “[It is like] history writ on lightning and my only regret is it’s all so terribly true.” Wilson claimed never to have made that remark. Perhaps it was his close friend and college roommate at John Hopkins, Thomas Dixon, also in attendance, who said it. Dixon wrote The Klansman, the novel on which the D.W. Griffith film was based. Griffith placed numerous quotes from Wilson’s History of the American People throughout the film. The book justified racial supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan. In it he wrote, “The policy of the congressional leaders (radical Reconstructionists) wrought a veritable overthrow of civilization in the South by their determination to put the white South under the heel of black South. The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.”

The film was widely viewed and riots broke out in major cities. Subsequently, it was denied release in Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Minneapolis. After viewing the film in Lafayette, Indiana, a white man killed a black teenager. A basking Dixon claimed, “The real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern audiences that would transform every man into a Southern partisan for life.”

Birth of a Nation seemed to have fulfilled its purpose. Nothing was more effective than reinvigorating the then dormant Ku Klux Klan, which used the film as a recruiting tool to bring in millions of new members from both the South and the North.

The NAACP fought back and made many unsuccessful attempts to remove the film from distribution and have it banned nationally, but the film remained extremely popular with white audiences.

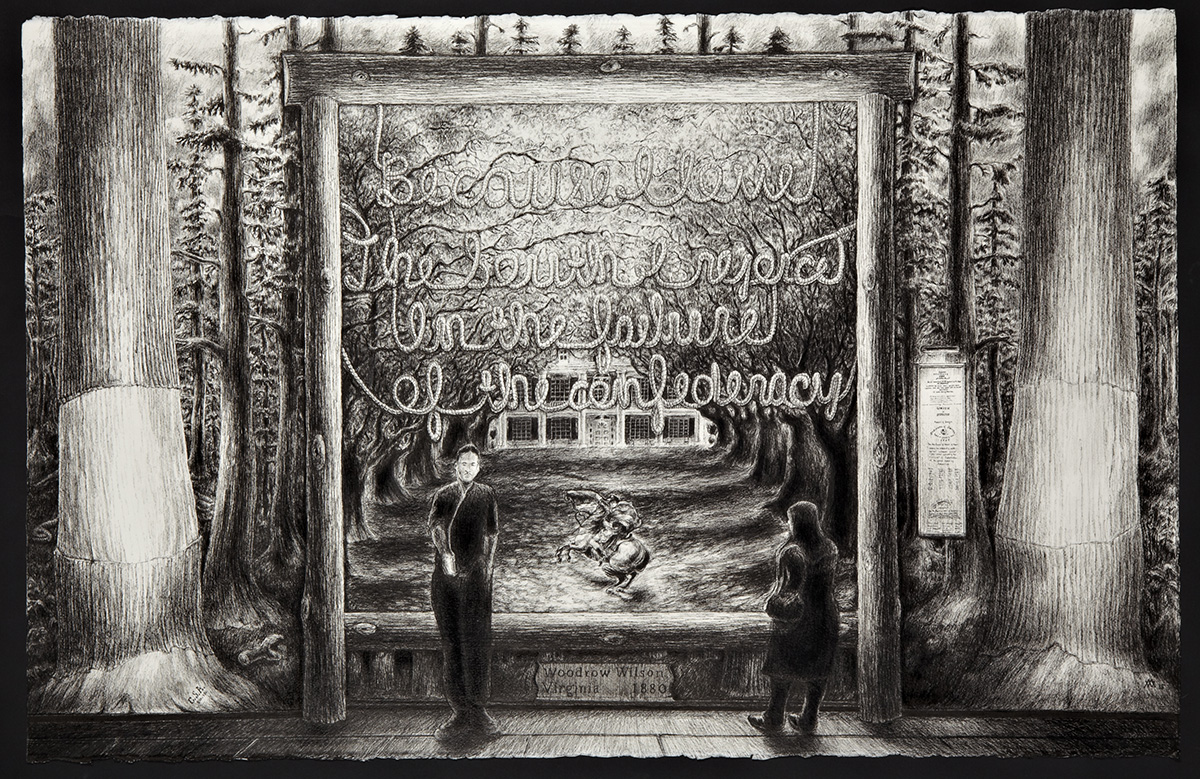

The Vindication of John Bright (2015)

Wilson had a great admiration for the liberal statesmen of Victorian England, most notably William Gladstone and John Bright. The context and meaning for Wilson’s confounding quote, “Because I love the South I rejoice in the failure of the Confederacy” is expressed again in cursive rope form, this time in front of a diorama typically found in a natural history museum.

The speech containing the above quote was given following Wilson’s first year as a law student at the University of Virginia in 1880. John Bright was an ardent supporter of the Union cause and rallied his fellow parliamentarians to prohibit the British Government from forming any alliance with or aiding the Confederacy in any form. Giving a paean to Bright to a white Southern audience just three years after the end of reconstruction was inviting both controversy and scorn.

Wilson very skillfully began his delivery, “I am conscious that there is one point at which Mr. Bright may seem to you to stand in need of defense. He was from the very first a resolute opponent of the cause of the Southern Confederacy.” Then Wilson would adeptly vindicate Bright by asserting his own Southern heritage explaining, “I yield to no precedence in my love of the South. But because I love the South I rejoice in the failure of the Confederacy.”

Wilson went on to explain that a rebel victory and the continuation of slavery would ultimately end in an economic and social disaster for the South. One wonders; is this what Wilson really believed?

The statement seems inconsistent with Wilson’s character. Ever a loyal son of the South, he would throughout his life express his Southern credentials. But Wilson was a very devout Presbyterian, and he had once considered becoming a minister. As a fervent and daily bible reader, he believed that God had ordained the extinction of slavery and the preservation of the Union so that American Democracy could shine as a beacon of hope for the rest of the world.

Wilson’s beliefs were not exceptional. In fact, he merely echoed the generations of statesmen who had preceded him. Jefferson, Clay and, of course, Lincoln worried that slavery tainted American Democracy. Jefferson was concerned for the souls of white men and fretted that slavery turned men into despots. Clay and Lincoln knew slavery to be inconsistent with democracy and the natural rights of man: That no man was entitled to deprive another man of the fruits of his own labor. Clay believed that the ultimate extinction of slavery would eventually come, but that slavery should until then be contained, a view that Lincoln shared up until the 1860s. But Lincoln was ever-evolving, though slowly, and in the last few years of his life would come to believe in gradual enfranchisement and eventual full rights and protections of citizenship for the former slaves.

“Nobody needs to explain anything about the South to me it is a part of the country I know.” The postbellum South that Wilson grew up in was a nation defeated. As an impressionable youth, he had experienced the spoils of war from the point of view of the vanquished. Throughout his life, he would continue to feel the sting of radical Reconstructionists intent on disenfranchising the leaders of the Confederacy.

Wilson wholly embraced ‘The Lost Cause’ of the Confederacy. It was Wilson who established the long-held tradition of sending a Presidential wreath to the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery each Memorial Day, one even President Obama is compelled to follow today. (To his credit, Obama has started a tradition of sending a wreath, likewise, to the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington D.C.)

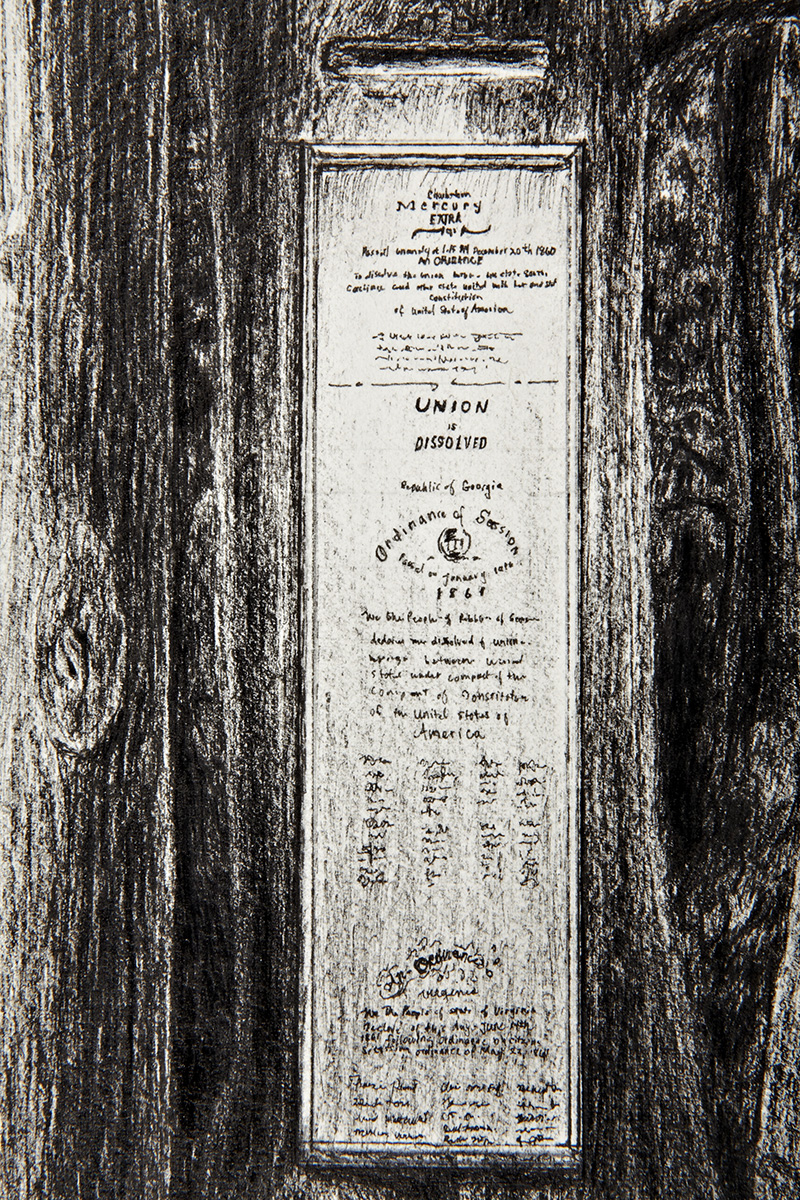

In 1913 Woodrow Wilson became the first Southern elected president prior to the Civil War. During his inauguration, Washington was crowded with Confederate revelers. The Rebel yell and renditions of Dixie rang through the streets. Dormant symbols of the old Confederacy became popular once more.

Today symbols matter as much as ever, especially in the wake of the racially motivated massacre on June 17, 2015. In the midst of a Wednesday evening Bible study, a racial supremacist named Dylann Roof who had surrounded himself with emblems of the Confederacy tried to ignite a race war in the sanctuary of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Because of his heinous and violent act of gunning down nine blacks, the Confederate flag above the capital in Columbia has been taken down, and the debate about the meaning of that battle flag has a new urgency.

Denial is the rampart to which hypocrisy clings. The defenders of the symbols of the Confederacy are oft to claim it’s about “heritage, not hate.” But to honor one's heritage does not give one license to expunge the truth. During their Secession Convention following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, members of the South Carolina delegation made it very clear that their reason for fighting was the right to continue to own human beings.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author A. Scott Berg wrote a biography of Wilson in 2013. Shortly after the book's release he gave a radio interview in which he explained Wilson's legacy, as he saw it. “Wilson believed in leveling the playing field. He believed this when he was fighting the club system at Princeton. But he was also fighting it through his administration; he was a man who felt that every American should have an equal shot at opportunity.” If that is so, then Wilson must have imagined African-Americans as something less than American.

A complete reckoning must require truthful accounting. By that accord, Wilson’s legacy of liberalism shall be forever tarnished by hate and bigotry—not liberal values at all.