“American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

James A. Baldwin

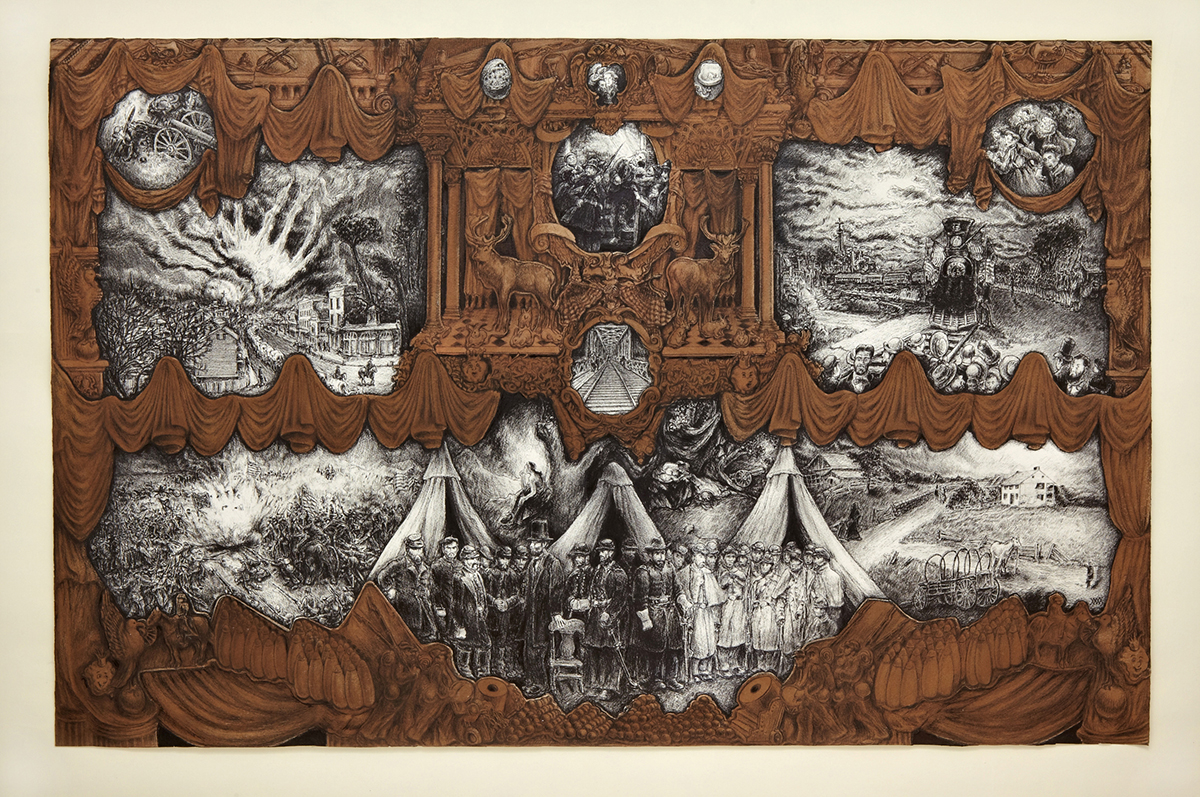

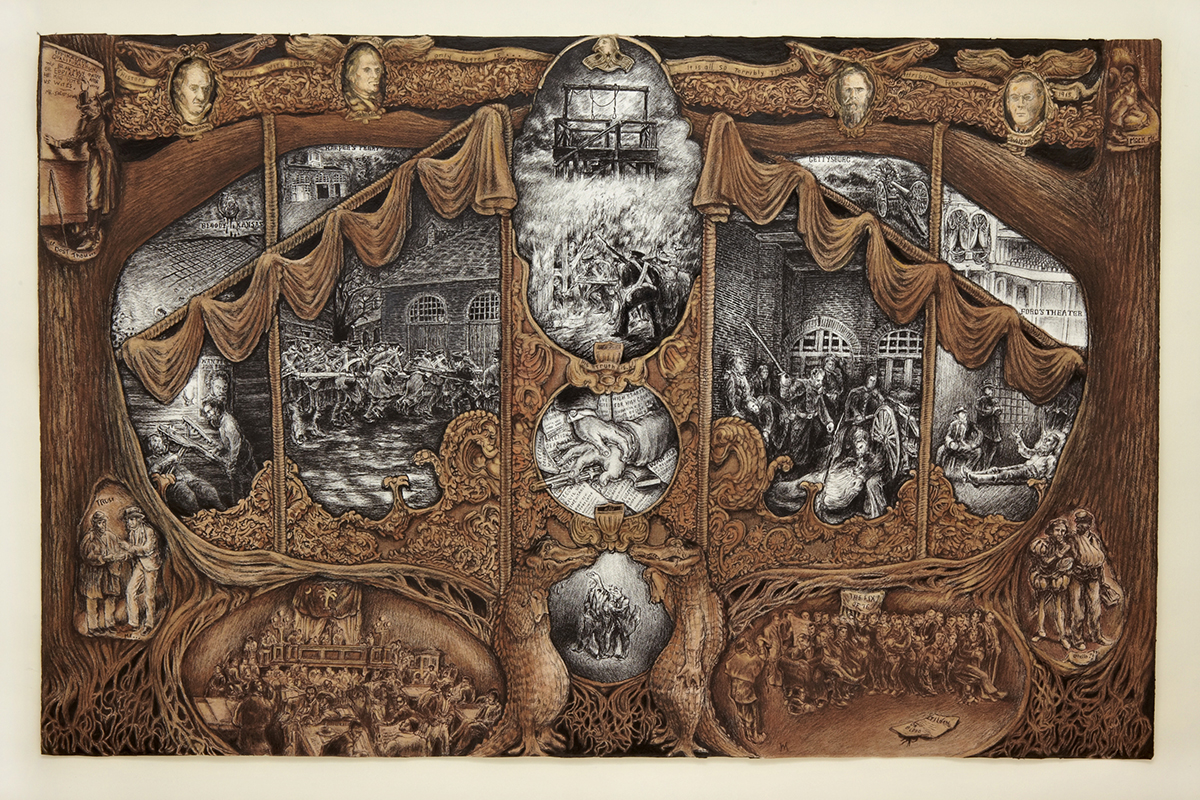

Bellum (2014-2015)

John Brown, the Civil War, Lincoln, and Reconstruction

D-type War (2014)

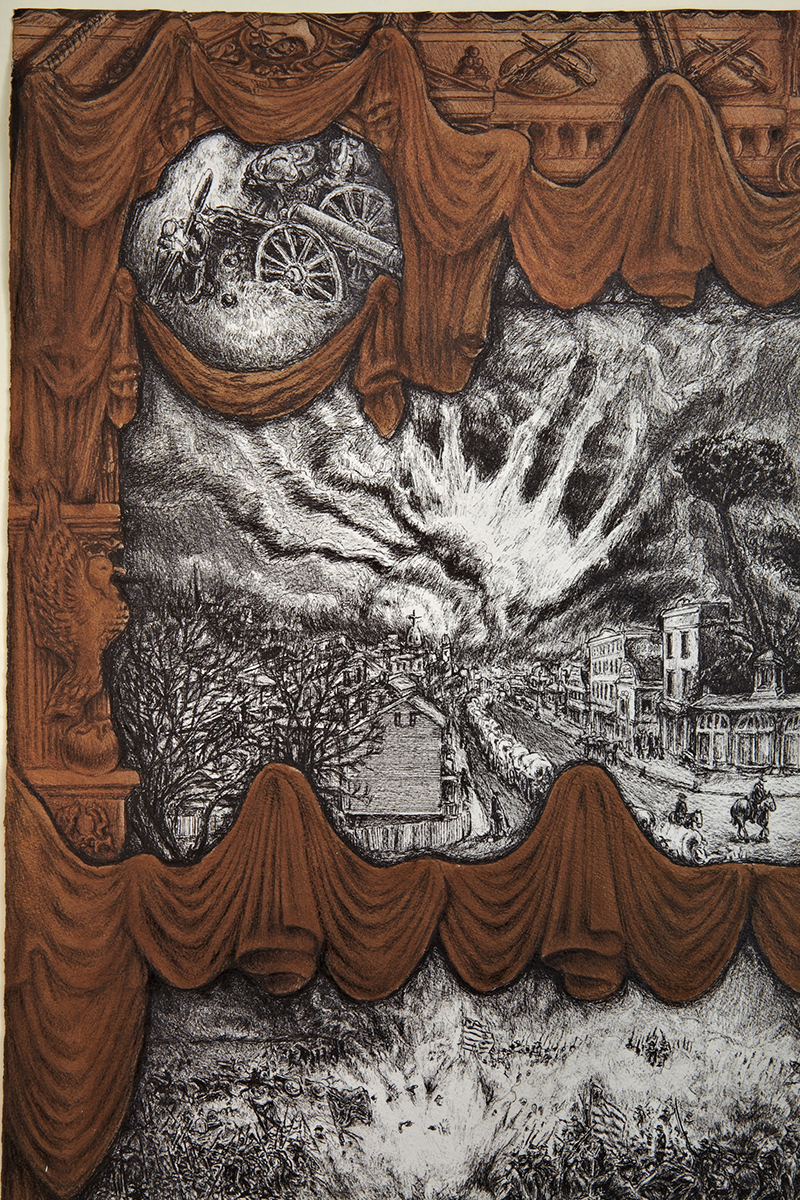

D-type War is an attempt to depict the epic sweep of the American Civil War, its prosecution, its human cost, and its political fallout.

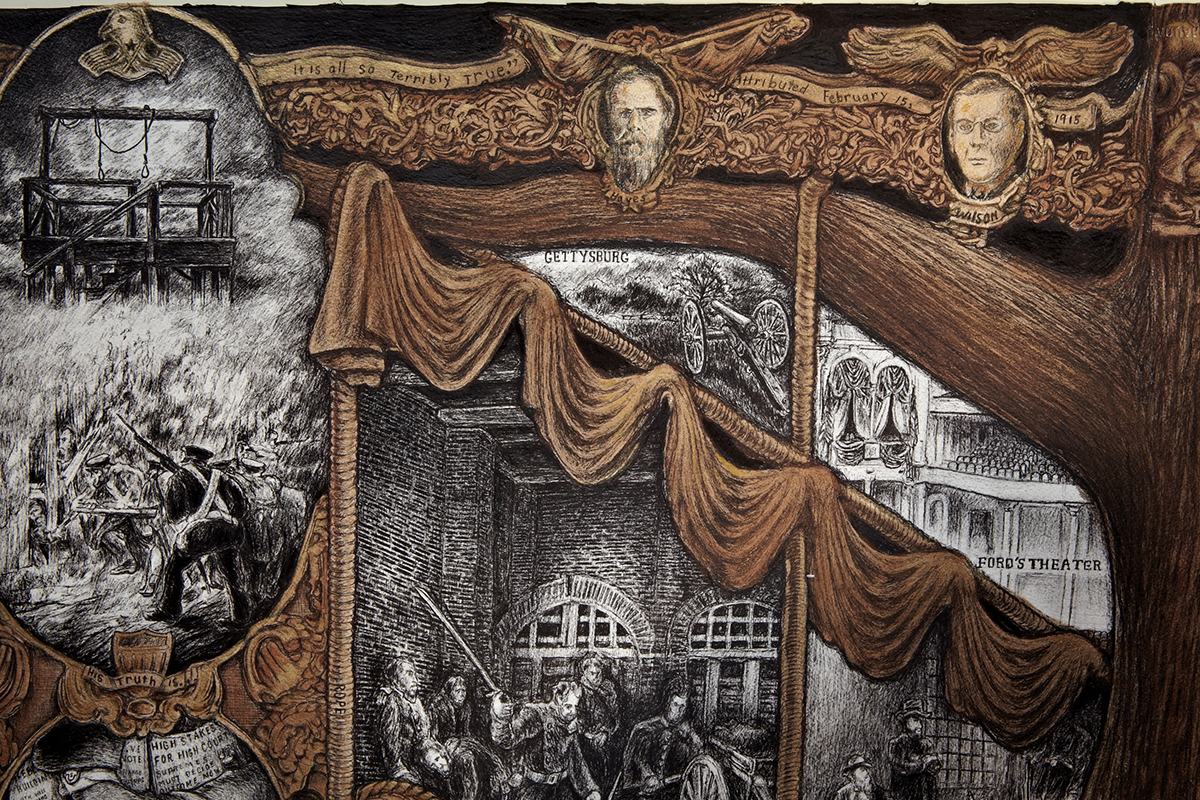

Portrayed in the top panel on the left is the siege and bombardment of Richmond, a city occupied by the Union forces late in the war. On the lower left panel is the confusion and horror of an actual battle scene. In the upper right is Lincoln’s funeral train. Complete with urban ruins in the background, its passing is witnessed by African American troops and an audience of white mourners. The exceptions are the two figures facing outward, Dred Scott and Homer Plessy, the plaintiffs in the most infamous Supreme Court civil rights cases of the Antebellum and Reconstruction eras. The Dred Scott decision of 1857 and Chief Justice Taney's narrow reading of the Constitution would further stir the cause of equity and push the nation toward war, while the Plessy vs. Ferguson case of 1896 would codify Jim Crow laws for another sixty-nine years.

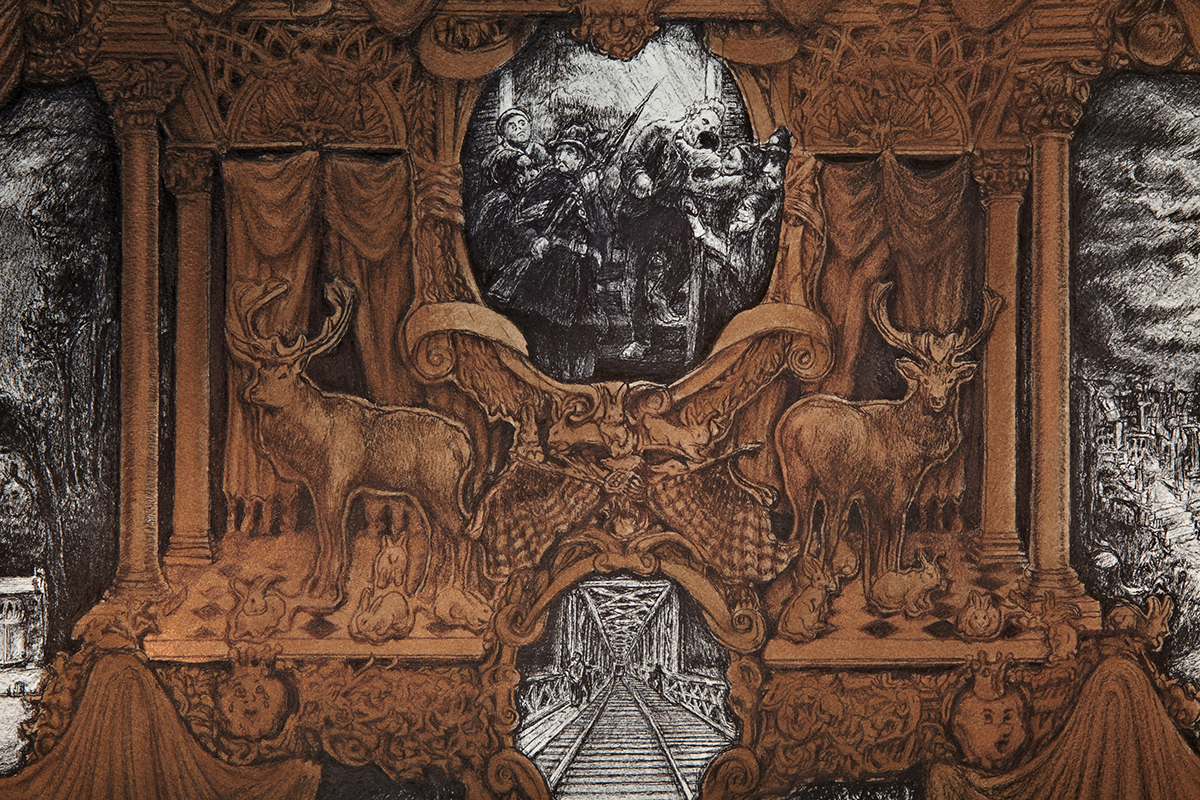

In the upper center is an image of John Brown from the painting, The Last Moments of John Brown, by Thomas Hovenden. It depicts the leader of the attack on the armory at Harper’s Ferry, thought by many to be the harbinger of the bloody war to come, being led away by his captors toward the gallows and his eventual martyrdom. In the midst of stags and hares, traditional symbols of renewal and rebirth, sits a railroad bridge, the sign of the next great industrial endeavor of the nation: the building of the Transcontinental Railroad.

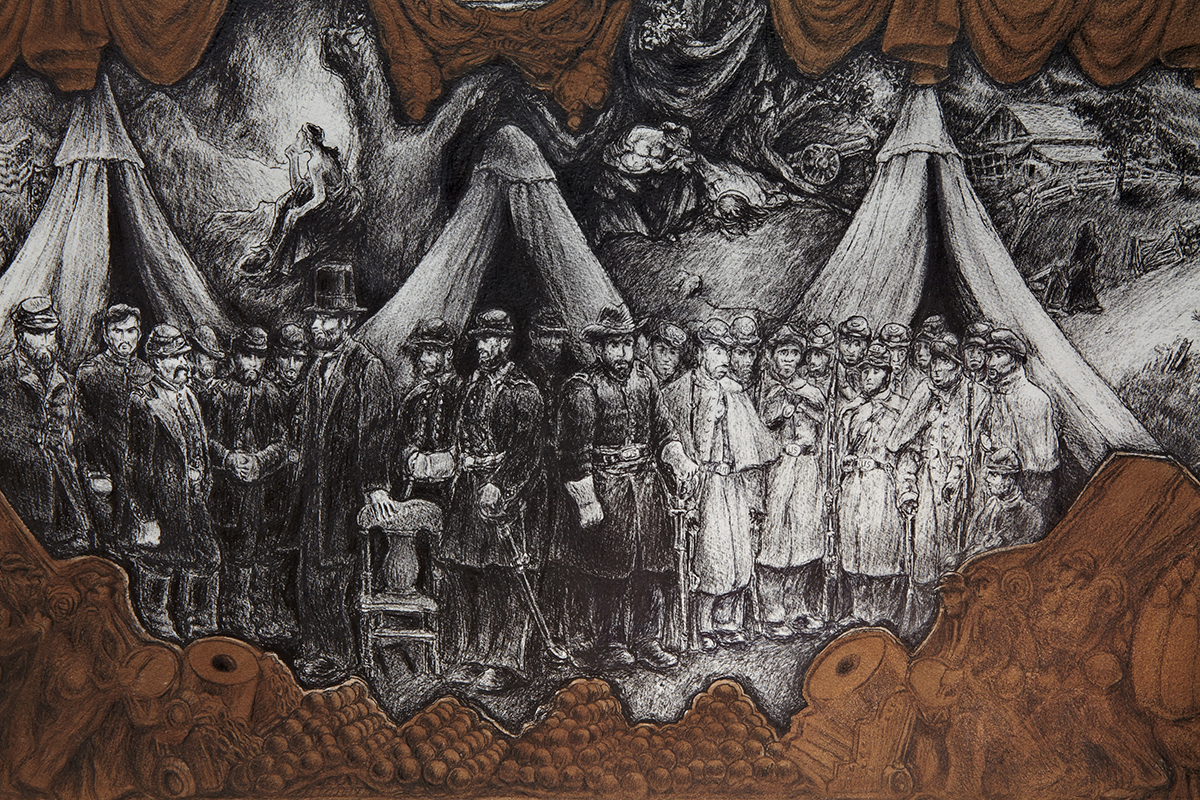

The two frames nearest the bottom are based on two Civil War photographs. The first is a well-known Alexander Gardner photo of Lincoln surrounded by General George McClellan and his staff. The second is based on a photograph that is both confusing and surprising, one of the black Confederate soldiers. The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was formed as a publicity stunt, a photo op, and a ruse, to mislead both Northern sympathizers and Southern loyalists into believing that fighting for the institution of slavery was a just cause. In truth, the laws of the Confederacy strictly forbade blacks from bearing arms and enlisting as soldiers. The Louisiana Guard and the few other Confederate slave regiments would readily surrender to the Union forces and fight alongside them as a people for whom the promise of equality, in Lincoln’s words, were “thus far so notably advanced” by the Civil War. Of course, they would not be fulfilled for another hundred years.

“John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see,

Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be,

And soon throughout the Sunny South the slaves shall all be free,

For his soul is marching on.”

William W. Patton’s 1861 version of John Brown’s Body

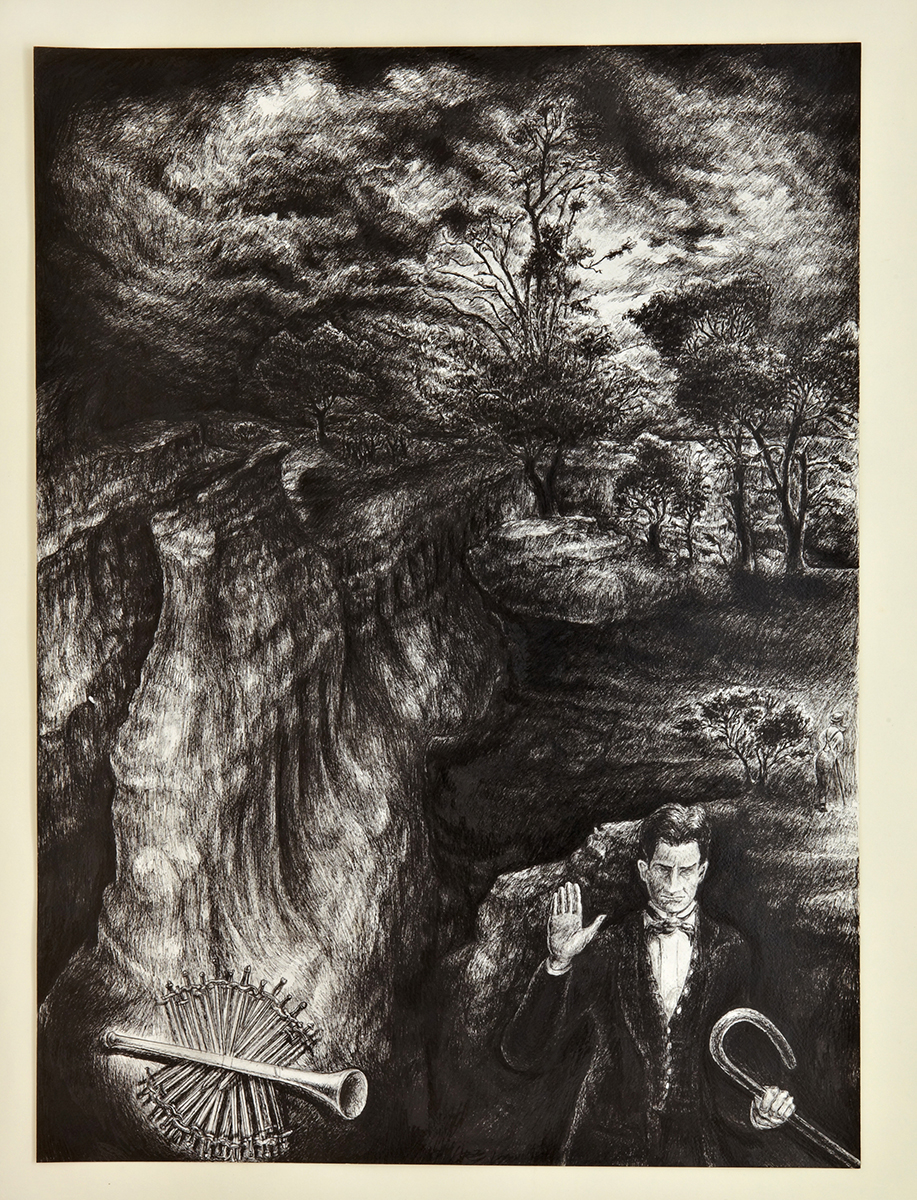

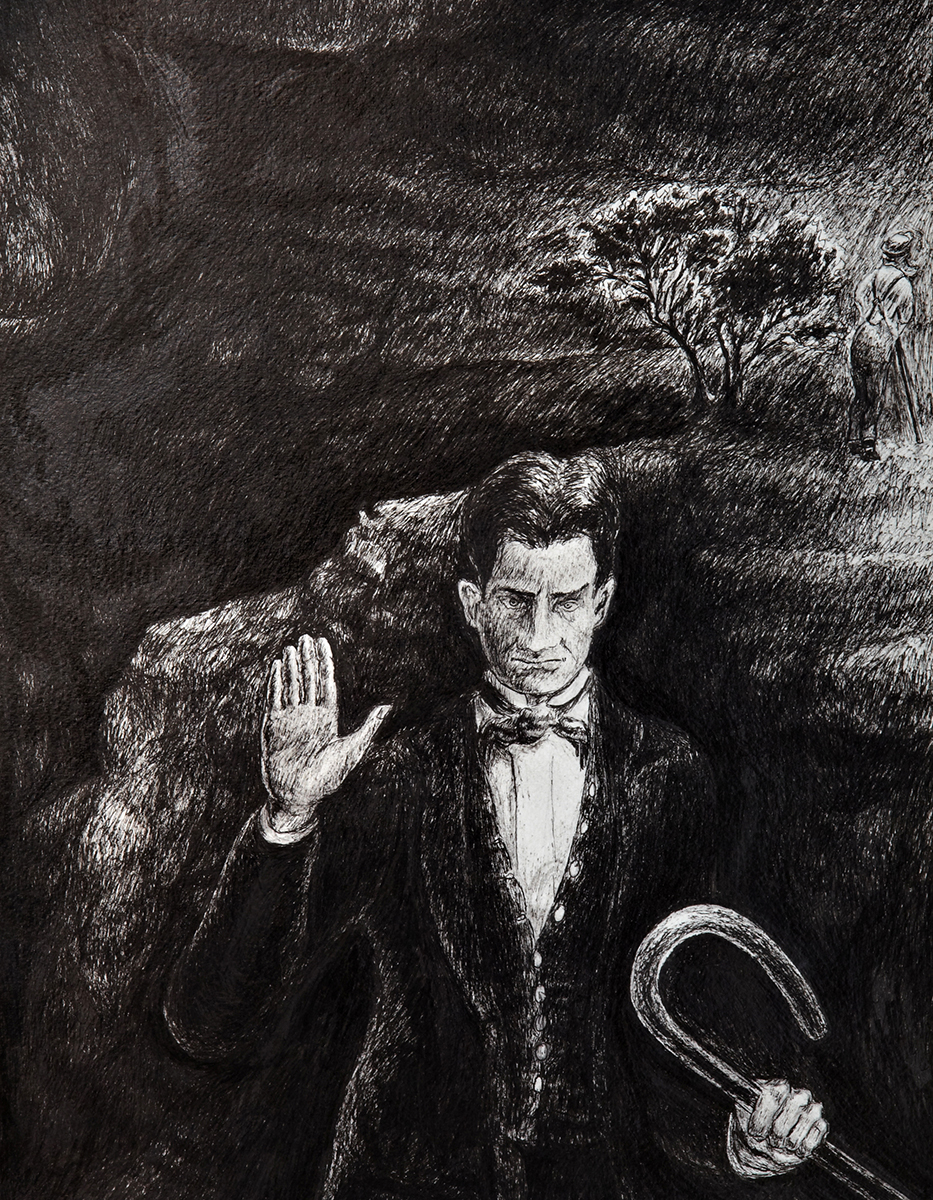

The Passion of John Brown (2014)

John Brown, the abolitionist firebrand, turned the course of the nation toward war in his raid of the Federal Armory at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, on October 16, 1859. Still seen as a polarizing figure today, the debate continues: Was he a freedom fighter or terrorist, a murderer or liberator? Until his bellicose actions in Kansas and his raid of the armory two years later, the abolitionist community was largely pacifist and considered, by its more ardent wing, well-meaning but wanting in vitality.

Thought of as a lunatic or, at least, a religious zealot by many historians, Brown’s fundamentalist faith bound in Old Testament scripture made his judgment of slavery unequivocal and uncompromising. Henry David Thoreau spoke in defense of Brown, while simultaneously shaming his complacent Northeastern brethren, when he claimed, “ They cannot conceive of a man who is actuated by higher motives than they are. Accordingly, they pronounce this man insane, for they know that they could never act as he does, as long as they are themselves.” Yet Brown’s friend and close advisor, Frederick Douglass, had his doubts and thought Brown’s plans for the raid poorly conceived. He warned him that he was walking into, “A perfect steel trap.”

Following Brown's capture, Governor Henry A. Wise, of Virginia, received numerous threats that bands of sympathizers―both black and white―were headed South to free Brown from his jail cell and carry out slave uprisings throughout the South. Suspicious people were jailed or run out of town by the local militias and the nearly 3,000 federal troops stationed around Charleston, where Brown was held.

John Brown quickly became the polarizing icon that would further divide an already deeply split nation. Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed Brown, “The new saint awaiting his martyrdom, and who, if he shall suffer, will make the gallows glorious like the cross.” Within weeks of Brown’s hanging. James L. Kemper, an assemblyman of Virginia, warned Northern sympathizers, “Whenever you advance a hostile foot upon our soil, we will welcome you with bloody hands and hospitable graves.”

For the South, where any attack on the institution of slavery was considered sacrosanct, Brown’s raid represented the true ambitions of the abolitionist North and would hasten the call for secession. For the North, John Brown would turn the abolitionist cause, once marked by non-violence and moral suasion, into the swords of absolution.

Bookends (2015)

Bookends juxtaposes the deeds of John Brown with the hope and heartbreak of Reconstruction. Collage-like, this work is a collection of re-rendered images: from the Reconstruction cartoons of Thomas Nast to the John Brown Wax Museum's staging of the most critical actions of the militant abolitionist, from the postcard-like pictures of historic monuments to the portraits of Presidents from James Buchanan to Woodrow Wilson.

The central panels detail Brown's role in the free-state vs pro-slavery violence known as Bloody Kansas, his raid of the armory in 1859, his capture, and imprisonment. His actions in Kansas would catapult him to national prominence.

John Brown (1800-1859) was a rarity for his era. He had given land to fugitive slaves, participated in the Underground Railroad, and raised a black youth as one of his own. He helped to create the League of the Gileadites in 1851, which gave safe refuge to runaways to protect them from slave catchers. Frederick Douglass was struck by Brown’s empathy and after meeting Brown for the first time in 1847 remarked, “Brown is in sympathy a black man, as though his own soul was pierced by the iron of slavery.”

Several events quickened the resolve of Brown and northern abolitionists in the 1850s, and would inevitably bring Brown and four of his sons to Kansas. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, strengthened the earlier law of 1793 by forcing citizens to assist in the capture of runaway slaves. Harboring or interfering with any escapee meant imprisonment and fines in the thousands of dollars. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 repealed the Missouri Compromise, which had previously prohibited slavery above the Mason-Dixon line. Now any new western territory would cast ballots to decide if its state would be free-labor or slave-labor. So divisive and contentious was the issue of slavery that members of Congress who spoke against it could be censored. Abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was nearly beaten to death on the Senate floor in 1856 by South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks for insulting pro-slavery Senator Andrew Butler.

Since the voters in the new territory of Kansas would now decide whether the state would become free or slave, proponents of both sides rushed to fill the territory with settlers who sympathized with their cause.

Like many others of his epoch, Brown believed in predestination―that God had chartered his course―which, for him, was to root out the evils of slavery wherever they may be. Armed with the wrath of his old Old Testament God and chafed by the injustice of slavery, there was no emollient in scripture. Now was the time to strike.

The panel on the far left portrays the massacre at Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas. On May 24, 1856, under the cover of darkness, Brown―leading a band of men calling themselves the “Northern Army”―entered three homes of proslavery men, removed five men, and executed them with broadswords. The following morning, the men's families would find their bodies strewn about the brush with heads split open, throats slit, one without fingers, another missing a hand, all bodies with gaping holes in them. A brutal carnage that easily compares to the work of Isis in contemporary times.

Brown's allies would defend his actions as just reprisals for the violence done to free laborers. When questioned, Brown said he approved of the killings but that he had not had any part in them. Years later, Salmon Brown would admit that his father ordered the slayings and, indeed, had shot one of the men.

Prior to Pottawatomie, there had been posturing, threats, and intimidation in Kansas by pro-slavers, but little violence. The battle for Kansas had begun, and Brown would be the one to draw first blood. His actions in Kansas would catapult him to national prominence.

The second frame from the left depicts the U.S. Marines under the command of Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart storming the engine house at Harper’s Ferry. In the panel directly to its left is John Brown, about to surrender seen at the side of one of his men who is dying of mortal wounds inside the engine house. In the last of the central panels is Brown among his jailers.

The raid at Harpers Ferry in October of 1859 was the result of many months of planning and preparation. Brown’s plan was to take hold of the Federal Armory and gather whatever weapons he and his men could collect. Then, as the news rapidly spread, slaves would rise up in rebellion and join forces with Brown’s army to liberate their brethren.

Despite a fortuitous outcome in Kansas’ guerilla warfare with pro-slavery forces and Missouri Border ruffians two years earlier, Brown had no military training. Propelled by earlier success and convinced that a Virginia slave rebellion would erupt once the myriad of oppressed learned of his seizing the Armory, Brown most likely believed that no force of militia or regular army could righteously oppose him.

On the evening of October 16, Brown was joined by seventeen of his twenty-two men (five of whom were black) and captured the armory. Initially, things went well. They cut telegraph wires and took control of the Baltimore & Ohio rail line, but the slave uprising Brown predicted never materialized.

Always righteous in his cause and rigid in his thinking, Brown never had a contingency plan. If his primary objective could not be met there was no plan B. Now without reinforcements, in the hours and days that followed, Brown and his raiders would be surrounded, trapped in the armory engine house, first by the local militia then the U.S. Marines.

Shortly before leaving his cell for the gallows on December 2, 1859, Brown handed his jailers a portentous note. It began with, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

In today's clinical opinions it is easy to say Brown was a narcissist, whose messianic complex was stirred by the flames of biblical prophecy. Truly, he was a man who put the prophetic above the practical, but it would not be the first or the last time in our country's history that a prophetic approach was used to confront and redress injustice.

Abraham Lincoln spent his formative years in the slaveholding state of Kentucky. Living close to the Cumberland Road, a route often used by the slave trade, Lincoln witnessed the horrors of slavery as a child. Later as a young man, he would revisit those horrors while working as a ferryman along the Mississippi River. Personally, Lincoln detested slavery, but he was no abolitionist; because he was able to portray himself as a moderate, he became the frontrunner for the Republican nomination in 1860.

Lincoln long contended that if he could save the Union while, at least, containing slavery, he would. Unlike John Brown, Lincoln was reflective and able to reconsider his views. Realizing in 1862 that it was expedient for him to free the slaves, many of whom had already freed themselves and were aiding the Union Army, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Shortly thereafter, Lincoln signed an edict that the now-free slaves should be received into the armed services of the United States. On one of the circulars, urging the new freedmen to enlist, were printed the original verses of John Brown's Body.

Abraham Lincoln, the once moderate, the man who so often put the practical before his own beliefs, the man Frederick Douglass once described as slow and tepid on race equality, had evolved into the prophetic. In his second inaugural speech he would mirror John Brown’s final words, exclaiming that if God so wills it, the battle will continue “. . .until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn by the sword.”

Within a month of his second inaugural Lincoln would be dead. His assassin, John Wilkes Booth, the man who had borrowed a mismatched uniform of a local militiaman so he could stand if the front row to view Brown’s hanging six years before. Now the Union had two martyrs.

Reconstruction was comprised of two periods. The first was Presidential Reconstruction (1865-1867). Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's successor and a native of Tennessee, insisted on leniency for the former leaders of the Confederacy and favored allowing individual states to decide the fate of their former slaves. Under Johnson, Black Codes were established throughout the South. In the beginning, Black Codes were a series of restrictive labor laws that encouraged the re-creation of a slave economy and discouraged free labor. The Codes soon took forms of coercive oppression. In 1866, the Ku Klux Klan was born and began its reign of terror throughout the South.

Threats, intimidation, and violence were regularly used to prevent blacks from participating in the political process. “White men alone must manage the South,” proclaimed Johnson.

The second period (1867-1877) was known as Radical Reconstruction. The Congressional Elections of 1866 brought radical Republicans to power. They sought to prevent the former “ruling class” from re-establishing control of the South. The South was divided into five military districts and under the protection of federal troops. Radical Republicans, both black and white, would demand that emancipation be followed by the full rights of citizenship, and the Fourteenth (1868) and Fifteenth(1870) Amendments would be ratified. For the first time, black men were able to vote and hold political office.

One of the cornerstones for the reform-minded radical Republicans, both black and white, was land redistribution.

The idea behind “forty acres and a mule” was first conceived by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and President Lincoln (the initial plan was for twenty acres). As the land of those in rebellion was seized by the Union forces, it would be given to the former slaves who had assisted the army or fought against their former masters. Lincoln had once doubted that there was a place for the former slaves in America and he had favored the idea of repatriating them. Again Lincoln showed flexibility of mind. Seeing the valor of the black troops and freedmen in defense of the union cause and knowing he could further demoralize the South, Lincoln had Stanton draw a blueprint for the Executive Order he would sign in 1863. But forty acres and a mule never really materialized. Though African Americans would initially benefit from political reforms under Radical Reconstruction, they would not see a significant economic power shift.

At the base of the tree trunk on the right is a wounded black soldier standing next to a plotting Iago, Othello’s trusted confidant-turned-villain. The sight of the black civil war veteran emboldened by his service and sacrifice became an augury of a new respectability and freedom that would emerge after the war. The Iago figure standing beside the soldier is President Johnson. Beholden to the interests of the wealthy planter class (his former sworn enemy), Johnson would continue to veto the portions of the Freedmen's Bureau Act comprising the promise of forty acres and a mule.

African Americans made great strides during Reconstruction and would win twelve seats in Congress. Nine in the House of Representatives and three in the Senate. In Louisiana P.B.S. Pinchback would be elected as Lieutenant Governor and later become Governor. In counties with large black populations, blacks held local offices and attained positions as county supervisors, sheriffs, magistrates, and school superintendents.

Ironically, it would be the low country of rice and cotton fields, the plantation country once held by the richest one percent of the planter class, in the states of Mississippi, Louisiana and South Carolina, where blacks would hold the highest number of political offices. In South Carolina, African Americans would hold the majority of seats in both houses of the state legislature throughout Reconstruction. In a panel on the lower left is my rendering of what an integrated South Carolina legislature of that time might have looked like.

The Reconstruction was mired in greed, and political patronage. Northern carpetbaggers and Southern scalawags affixed their fortunes to black and white radical Republicans and let their own personal gain come before reforming the former slave-holding south.

Pictured in the panel on bottom left is another political cartoon (also by Nast of the era, though not of Reconstruction) of Boss Tweed and his minions, the symbol of cronyism and corruption that was rampant during the period and undermined progressive strides of the Reconstruction.

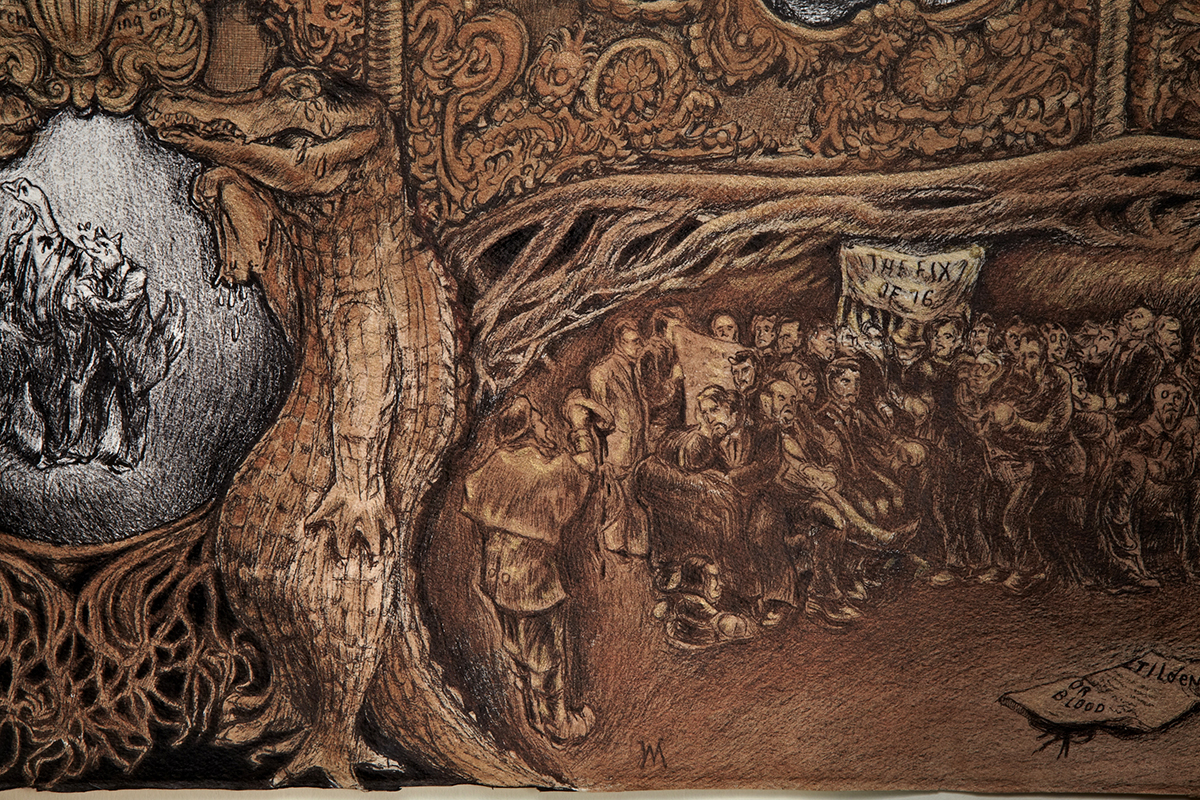

The controversial presidential election of 1876 would decide the fate of Reconstruction. In the center panel is my reinterpreted version of Nast’s cartoon complete with an analogy of the 2000 Presidential Election.

In 1876, Samuel Tilden, the Democratic Governor of New York, won the popular vote, while the Republican candidate, Rutherford Hayes, had won the most electoral votes. The controversy hinged on nineteen electoral votes all from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina―former Confederate states still under Republican-mandated military occupation. The Democratic electors insisted that a corrupt electoral board had overturned the popular votes by the Democratic majority and had rewarded them to Republicans. A Constitutional crisis arose and armed threats were made by some on the Democratic side.

The Federal Electoral Commission was convened, consisting of members of Congress and the Supreme Court, in a 8-7 decision the Commission gave all the contested votes to Hayes. Created to pacify bitter Democrats and prevent a second violent rebellion, the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction. Heartbreakingly for African Americans, the promise and progress of Reconstruction would be deferred. The country, still besotted by the legacies of slavery and racial injustice, again would have to wait.

Scrolled above are the attributed comments of Woodrow Wilson after viewing the egregiously racist film Birth of a Nation.

In 1912, Woodrow Wilson would become the first southern-bred Democratic President elected since James Polk. Wilson is often remembered for his progressive policies, but the former Princeton university president and Governor of New Jersey was a true son of the South. Wilson spent his formative years in Georgia and the Carolinas living in the shadow of Reconstruction. His college roommate, Thomas Dixon, was the author of The Klansmen, the play on which the film Birth of a Nation was based. The play and film justified the violence of the Ku Klux Klan, considered necessary to control the greedy ambitions of the newly enfranchised blacks and to protect white women against what was considered the uncontrolled sexual proclivities of a lustful race.

In 1915, Birth of a Nation was the first feature film ever viewed in the White House. After seeing it, Wilson supposedly remarked that the film was, “History writ on lightning and my only regret is that it is so terribly true.” Wilson’s comments, at once damming and ambivalent, would later be disavowed by him. But during his administration, the Klan had a rebirth and membership swelled. Over the next two decades, the number of lynchings would grow tenfold and were not just limited to the South. The Klan was no longer a regional clandestine terrorist organization, but now a national one.

In 1881, Frederick Douglass, orator, publisher, and once fugitive slave, went to Harpers Ferry to speak at the fourteenth anniversary of Storer College. The college had been created to train black teachers, the first of its kind in the South. On its grounds sat the old armory engine house, “John Brown’s Fort.” There Douglass eulogized his friend’s convictions, saying, “His zeal for my race was greater than my own. It was the burning sun to my taper light. I lived for the slave but he died for the slave.”

Douglass would also express the sentiment that many would come to share, “John Brown could not end the war that ended slavery but he did at least begin the war that ended slavery.” Then, he echoed Brown’s last prophetic words as Lincoln had in his second inaugural, declaring that the crimes of the nation had to be paid for and that the national explosion which Brown had lit was, “The answer back of the avenging angel for the midnight raids of Christian slave traders on the sleeping hamlets of Africa.”