Stinkin' Lincoln

“Mr. Lincoln, Mr. Lincoln,

What the heck have you been drinkin’?

Is it whiskey? Is it wine?

Oh my God, it’s

Turpentine!”—anonymous children’s rhyme

“These was all nice pictures, I reckon, but I didn’t somehow seem to take to them, because if ever I was down a little they always gave me the fantods.”—Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

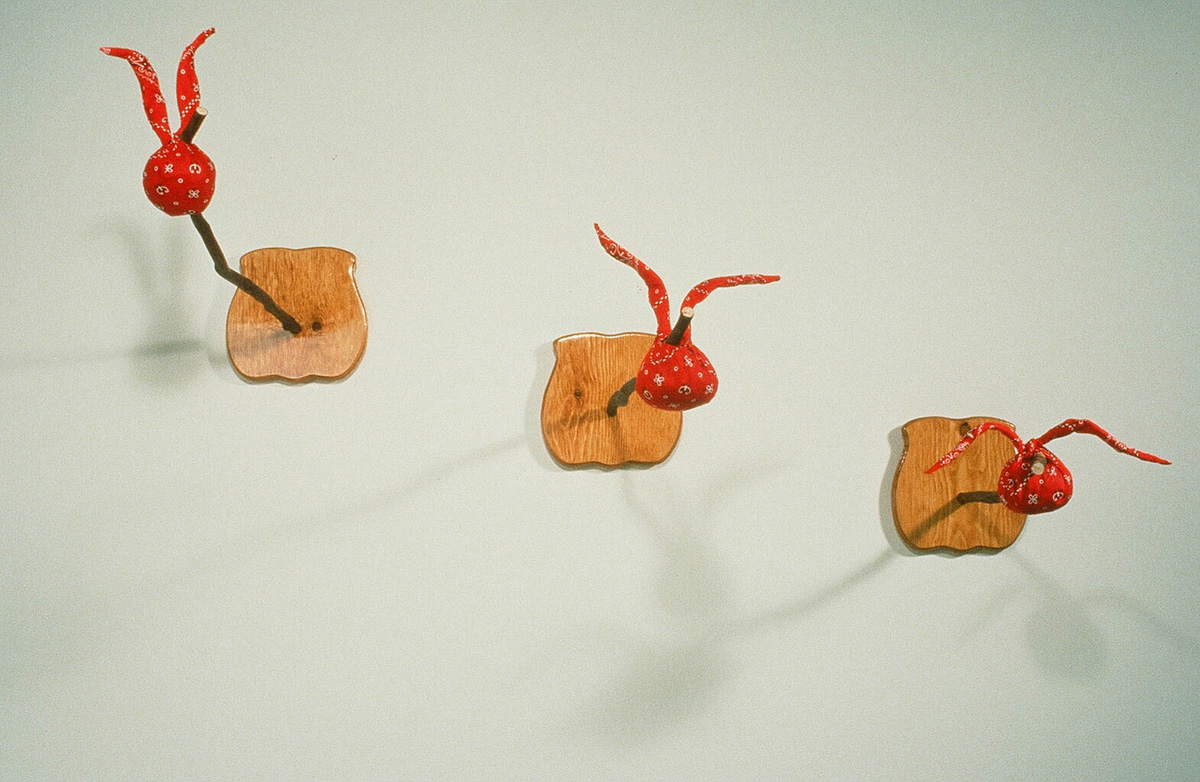

Will Miller’s new body of work at the Lab Gallery uses nostalgic icons from early American history, simultaneously re-mythologizing them and debunking them in a way which tacitly comments on contemporary social concerns. The installation consists of three parts: a series of wall-hanging Hobo Trophy constructs, and two free-standing sculptures which embody, among other materials, a barrel and a twelve-foot rowboat. Although each piece is constructed from modern-day, ready-made objects, numerous components have been carefully manipulated and reworked to look antique.

Hobo Trophy (1991)

Miller’s hobo bags almost seem real; with their rustic appearance, they evoke a passage in United States history in which the American Dream—maverick entrepreneurialism, times when a man had the freedom to pull up stakes and seek out his fortune—was something more than a hazy, media rendered cliché. Who were the men who carried these makeshift suitcases? They were visionaries: outlaws, drifters, folk singers, union men who boldly spread their message from town to town. With all their worldly possessions slung over their shoulders they were more than just survivors—they were free spirits, untethered by the responsibilities of family life or a steady job. They knew that opportunities abounded and were theirs for the taking…

Miller’s work also reminds us that this is just so much bullshit. Then, as now, indigence is an unromantic, unsettling reality. And while the Kerouac mythos still thrives today, we know better than to think of Miller’s Hobo Trophies as anything more than the historic equivalent of a stolen super market shopping cart.

Dell (1991)

Indeed we might similarly examine Will Miller’s reworking of the classically comedic barrel and suspenders motif. He anthropomorphizes this surreal hard-luck costume with a pair of worker’s boots, and implies narrative with a pile of plastic apples (a move prompted by logistics, but also a reminder of the cultural artifice being questioned). Miller's sculpture suggests free enterprise that is an ambitious street-corner huckster making the best of it during tough times. But to the thoughtful urban viewer, these apples are little better than “Street Sheets,” and as such, undermined the unlikely rags-to-riches scenario that American cinema has equated with this iconography ever since the Great Depression.

Betty (1991)

In contrast, the centerpiece of Miller’s installation Betty, reads as homage to leisure. Like the other pieces here, narrative abounds: summer is over, a suitor rows an elegant lady through a pastoral setting while a fur muff protects her hands from the autumn chill… Betty, like the rest of the work here, is satisfyingly whimsical, at least on the surface. It is not unlike a car advertisement, albeit charged with a sinister edge.

The most troubling, and ultimately compelling aspect of Miller’s installation is the haunting sense of melancholy and absence that it engenders. While these contrived relics function as sculpture today, it is not difficult to imagine them in the service of real people during a time which was certainly no less free from human need. Miller’s work reminds us that bygone eras are not necessarily the idyllic times that we sometimes pretend they were, especially during periods of contemporary strife.

When Huck Finn expresses this discomfort with the portraits at the Grangerford house, it is because they are images of the dead. Like Huck, we may feel an uneasy sense of mortality when confronted with Miller’s objects—for the lives of the hobos, street vendors and society ladies that they pretend to document. By creating an ironic portrait of America’s past, Will Miller’s Lab installation provides us with an opportunity for reappraising ourselves, and the lives and struggles of those around us.

Charles Gute, 1991